By 2016, Afropop had perfected its formula: sun-drenched melodies, thumping percussion, and hooks engineered to melt seamlessly into Lagos traffic. But then came Cruel Santino’s Suzie’s Funeral, an album that arrived like a cryptic transmission from the underworld—shadowy, genre-fluid, and gleefully uninterested in playing by the rules. If Afropop was a well-lit stage, Cruel Santino (then Santi) was the kid in the rafters, filming a cult classic on a VHS camcorder.

At the time, Suzie’s Funeral didn’t sound like an event. It wasn’t built for radio or club dominance. But in retrospect, it was a quiet revolution. It cracked open the rigid structure of Nigerian pop, stretched it into something unpredictable, and gave an entire generation permission to be weird. Here’s how this off-kilter, lo-fi fever dream became an Afropop rebirth.

1. It Sounded Like the Future (But From a Parallel Dimension)

Even now, Suzie’s Funeral doesn’t sound like anything else. It’s hazy, hypnotic, and oddly weightless—like a soundtrack to a movie that doesn’t exist. Cruel Santino took dancehall, R&B, punk, and alt-rock, tossed them into a blender, and poured out something warped and intoxicating.

On Gangsta Fear, he and Odunsi (The Engine) croon over a skeletal, brooding beat that feels like it was found on an old cassette in a neon-lit alleyway. Jungle Fever takes the DNA of Afropop and mutates it into something eerie and cinematic. Instead of sharp, radio-polished hooks, the melodies drift and dissolve, like smoke curling under a dim club light.

Afropop has always been about big sounds—booming drums, crisp highs, bright vocals. Suzie’s Funeral refused to be big. Instead, it lurked, whispered, and loomed, proving that restraint could be just as powerful as excess.

2. It Gave Nigeria Its First True “Alté” Anthem

Before alté was a movement, it was a feeling—an unspoken understanding among a generation of Nigerian youth who felt a little left of center. Gangsta Fear became their unofficial anthem. It wasn’t loud. It wasn’t demanding attention. But it radiated cool.

With its ominous synths and hypnotic vocal layering, the track sounded like a secret. It was the kind of song you stumbled upon in the depths of SoundCloud and immediately texted to your closest friends like a classified discovery. Cruel Santino and Odunsi weren’t performing—they were vibing, murmuring cryptic lines like they were passing notes under the table. If mainstream Afropop was a bright LED billboard, Gangsta Fear was a flickering neon sign in an abandoned warehouse.

3. Dancehall Became a Playground, Not a Blueprint

Nigeria has always had a complicated relationship with dancehall—adopting, reshaping, and rebranding it as part of the Afropop machine. But where many artists leaned on dancehall for club-ready bangers, Cruel Santino treated it like a loose suggestion rather than a formula.

Suzie’s Funeral wasn’t trying to be Jamaican or Nigerian—it was trying to be otherworldly. Cruel Santino’s use of patois was fluid and irregular, slipping in and out of phrases like a stoner mumbling secrets. His beats weren’t meant for wining in the club; they were made for cruising through humid streets at 2 AM, replaying conversations in your head that never made sense in the first place.

4. The Visuals Didn’t Just Accompany the Music—They Expanded It

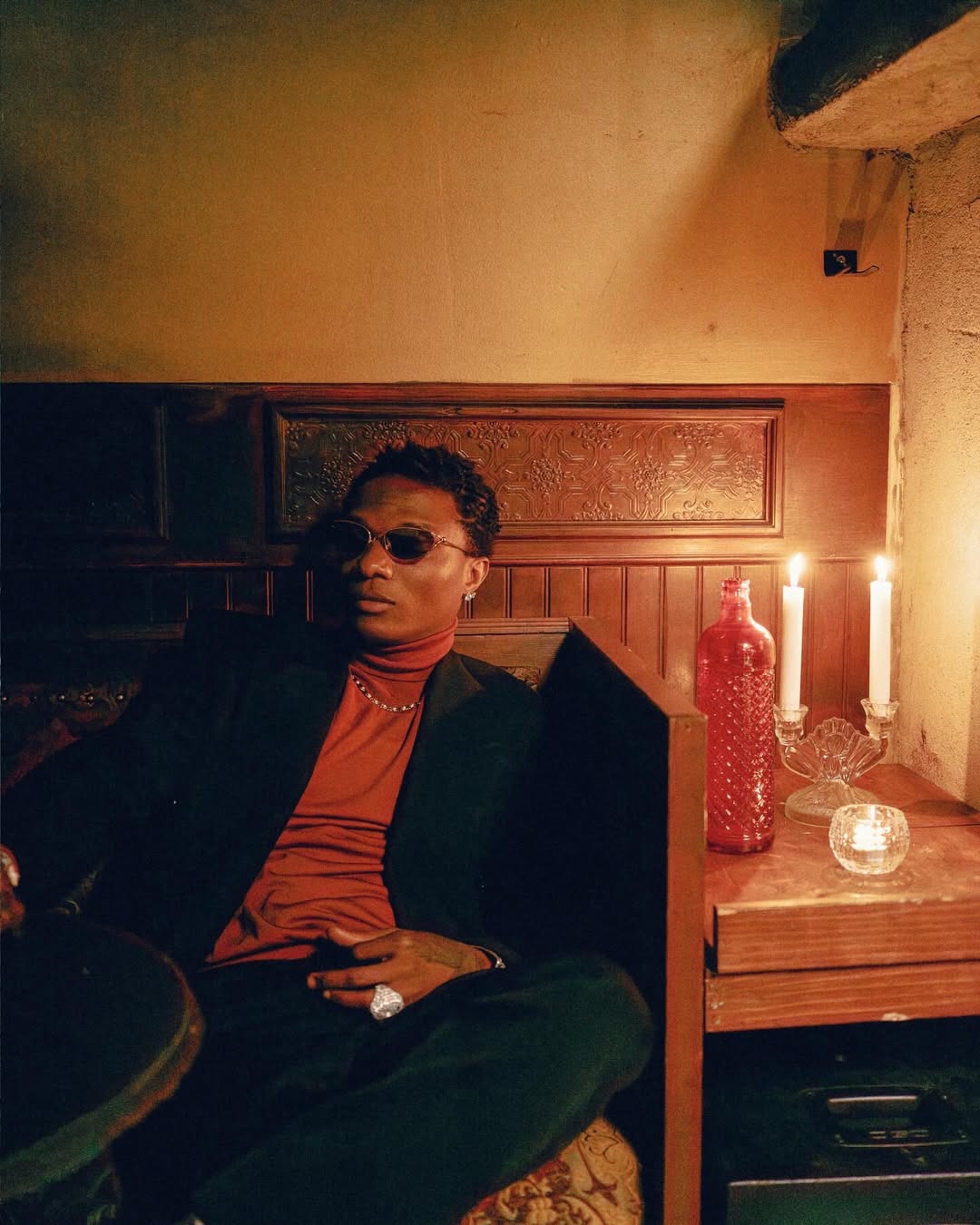

Cruel Santino has never been just a musician. He’s a world-builder, an auteur, the director of his own cryptic universe. The videos that accompanied Suzie’s Funeral weren’t just promotional material—they were invitations into a self-contained mythology.

With lo-fi textures, horror-movie aesthetics, and fashion choices that looked like they were thrifted from an underground punk shop in Tokyo, he carved out a space where being Nigerian meant whatever you wanted it to mean. Suddenly, alté wasn’t just a sound—it was a subculture.

5. The Songwriting Was a Controlled Chaos of Slang, Codes, and Unfinished Thoughts

Trying to analyze Santino’s lyrics is like trying to decipher the scribbles on a teenager’s notebook. They’re fragmented, half-muttered, and often indecipherable—but that’s the point.

On Jungle Fever, he sings, “Why you dey form for me? / Why you dey run from me?” in a way that sounds less like a confrontation and more like a passing thought. Lines drift in and out of clarity, delivered with a nonchalance that makes them feel even cooler.

While mainstream Afropop relied on sharp hooks and clean phrasing, Santino was mumbling and warping his vocals, treating words like brushstrokes in a larger, messier painting.

6. It Rejected Afropop’s Formula—And Won Anyway

By the mid-2010s, Nigerian pop had a well-oiled system: glossy production, crisp percussion, and melodies engineered for instant replay value. Suzie’s Funeral ignored all of that.

The beats felt raw and unpolished. The vocals were drenched in reverb, often mixed so low they felt like whispers. The melodies didn’t follow predictable patterns—they snaked and unraveled, sometimes disappearing entirely.

Yet, against all odds, Suzie’s Funeral found an audience. Not through radio play. Not through corporate sponsorships. But through word-of-mouth, internet discoveries, and a sense of ownership among a generation of kids who had never seen themselves reflected in Nigerian music before.

7. It Was the Blueprint for a New Kind of Nigerian Star

Santino wasn’t trying to fit into Nigeria’s music industry. Instead, he forced the industry to expand around him. Suzie’s Funeral made room for artists who didn’t fit the mold—artists like Odunsi, Lady Donli, Tay Iwar, and even a pre-stardom Amaarae.

Years later, you can hear its DNA in Tems’ moody vocal stylings, in Rema’s genre-blending experiments, in Omah Lay’s laid-back delivery. Afropop today is far more fluid than it was in 2016, and that’s partially because Suzie’s Funeral proved there was space for something other.