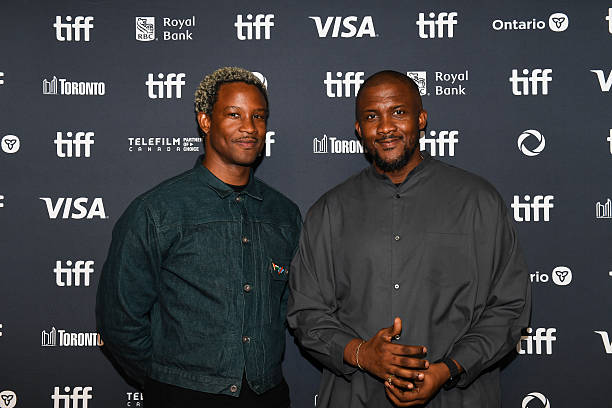

Bomi Anifowose

In the quiet corridors of museums and the expanding reach of the digital world, a new kind of cultural movement is taking shape. African heritage is not just being preserved but actively protected and reimagined for the future. At the center of this shift is Adaobi Orajiaku, a blockchain engineer and founder of Atsur Technologies. Her work is challenging how we think about ownership, value, and legacy in the African art market, where forgery and broken systems have long diluted the impact of homegrown creativity.

For many African artists, the problem isn’t talent or relevance. It’s proof. Proof of authorship. Proof of originality. Proof that their work has value beyond applause. Without formal systems of authentication, artists are often excluded from the long-term benefits of their own creations. Orajiaku’s answer to this is rooted in technology. Through Atsur, she uses blockchain to give African artworks a digital fingerprint—one that can’t be altered, duplicated, or ignored.

Her approach recently got a major co-sign from the Nigerian government. In collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Atsur is working to digitize over 3,000 pieces from the national archive. But despite the institutional backing, Orajiaku’s focus is personal. Her mission is to build tools for artists first, not just for collectors, museums, or tech insiders. That mindset also drives her other initiative, Akara Africa, a web3 community helping more young Africans step into the future of cultural tech.

In this interview with Upper Entertainment’s Sijibomi Anifowose, Adaobi Orajiaku breaks down how blockchain is doing more than protecting art—it’s protecting artists. She shares the thinking behind her work, what it means for Africa’s cultural economy, and how technology can be used to rewrite the rules of legacy and creative ownership.

Upper: Let’s begin with your origin story—what personal or professional experiences led you to founding Atsur Technologies?

Adaobi: As a blockchain engineer and art collector, I noticed a glaring gap in how African art was authenticated and protected. Atsur was born from a desire to bridge that gap and offer artists better control and recognition.

Upper: Before Atsur, you had a strong background in software engineering and blockchain consultancy. How did these technical skills shape the unique model you’ve built for African art authentication?

Adaobi: My technical background gave me a deep understanding of blockchain’s potential, particularly its power to secure records and build trust. I saw how underutilised it was in the African art space and how, if applied well, it could solve real structural problems in the industry.

Upper: You’ve spoken about solving the “fragmentation” of the African art market. In your view, what has most contributed to this fragmentation, and how does blockchain provide structural solutions?

Adaobi: Colonialism led to the loss and mismanagement of African art data. Many galleries still operate with outdated or poorly resourced systems, making records easy to lose or unreliable. Blockchain offers a transparent, tamper-proof system where every verified player in the Atsur Verification Alliance Network can contribute and trust the data.

Upper: Atsur’s system gives artists ownership proof, royalties, and resale benefits. How does this practically work for the average artist—especially one in a rural or informal creative ecosystem?

Adaobi: Traditionally, visibility and fair compensation were reserved for artists discovered by galleries or international organisations. Now, any artist can sign up, document their work, and receive blockchain certification. Their work becomes verifiable, trackable, and eligible for royalties through our network partners. This verification builds trust with collectors and helps artists earn more.

Upper: Nigeria’s National Gallery of Art recently partnered with Atsur to digitise over 3,000 artworks. What were the biggest challenges and learnings from that process?

Adaobi: We’ve learned that government processes move slowly, but this reinforces the private sector’s responsibility to lead meaningful change. We were also reminded of Nigeria’s rich artistic heritage. It’s an honour to contribute to preserving and validating it for future generations.

Upper: In a space where artists are often left behind by tech-driven solutions, how is Atsur ensuring accessibility and education around blockchain for creatives who are not digitally fluent?

Adaobi: We’ve created initiatives like Artivism, which trained artists to use tech tools to amplify their work. Atsur also abstracts the complexity of blockchain, artists don’t need to understand the technical layers. Our platform lets them access features like royalties and verification without needing prior tech knowledge.

Upper: Can you share a specific story of an artist or artwork whose journey was transformed through Atsur’s verification system?

Adaobi: We’re gearing up to launch the Atsur Verification Network, which will allow verified artworks to be listed for sale or resale through our partner platforms. While we’re still in the early rollout, we’re already seeing growing interest and adoption by artists eager to secure and monetise their work.

Upper: Beyond authentication, what other possibilities does blockchain unlock for the future of African cultural heritage—perhaps in areas like provenance, valuation, or community engagement?

Adaobi: Blockchain lays the foundation for trusted provenance, real-time valuation data, and decentralised engagement. It can revolutionise how communities participate in preserving and owning their cultural heritage.

Upper: You also founded Akara Africa, a Web3 community. How does this initiative intersect with your mission at Atsur, and what has its reception been like among African tech talents?

Adaobi: Akara Africa actually inspired Atsur. Through Twitter Spaces and NFT discussions, I realised the potential of Web3 in solving real-world problems. Every tech built for and by Africans expands our ecosystem. Atsur is an infrastructure that we hope others will build on it, creating more opportunities for artists and developers alike.

Upper: There’s often skepticism around the use of blockchain in developing economies—how do you respond to concerns about sustainability, scalability, or technological elitism?

Adaobi: We’re addressing this through public education campaigns and by demystifying blockchain. Our approach focuses on real, accessible use cases, not hype, so people can see how it works for them, not just around them.

Upper: How do you envision the role of policy or government support in scaling blockchain-backed cultural preservation efforts across the continent?

Adaobi: Governments have a key role to play in regulation and support. Clear, thoughtful policies can help ensure that blockchain solutions are safe, ethical, and scalable while enabling innovation in the cultural sector.

Upper: In your ideal future, what would a thriving, blockchain-integrated African art ecosystem look like in the next 10 years?

Adaobi: A future where African art is traded seamlessly on global exchanges, serves as collateral, and generates sustainable income for generations. Verified provenance and digital ownership will become standard, and artists will no longer need to leave the continent to be globally recognised.

Upper: Lastly, for young African women aspiring to merge tech with cultural innovation, what’s one lesson from your journey you hope they take with them?

Adaobi: Be consistent. Believe in your vision, even when others don’t see it yet. Use feedback to refine your path, but stay the course. You can build something real.